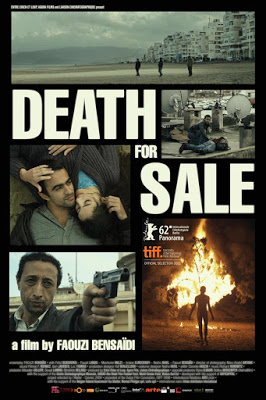

Religion, Materiality and Machines in Faouzi Bensaïdi’s Death for Sale

Rebecca Moody interprets Bensaïdi’s 2011 film, Death for Sale, using a variety of perspectives; from the ways that religion influences the materialization of political and economic structures—especially in relation to state institutions—to the link between broken (or breaking) institutions and broken (or breaking) lives, as informed by Deleuze and Guattari, to the struggles of Muslim women in rapidly changing societies. The film uses subtle visual techniques and minimal dialogue to convey the conflicts and fragmentation that commence when two (or more) starkly different ways of life are forced into an uneasy alliance too quickly.

What does it mean to read religion in the materiality of human bodies not as they engage in prayer or ritual but as they index a tradition’s political and cultural iterations? Here I argue that, in Moroccan director Faouzi Bensaïdi’s 2011 film Death for Sale, the material body of a (female) character indexes political Islam and contemporary Muslim-majority Morocco in a context of globalization. While Death for Sale is set in Morocco - officially the Sharifi Kingdom of Morocco, marking the monarchy’s lineage dating to the Prophet Mohammed - it absents even while it indexes Islam_._ We never see a mosque, never watch a believer perform ablution or pray. Yet, as is so often the case, we can see the intersection of religion and politics played out on Muslim women’s material bodies.

In a September 2014 Material Religions post, David Morgan insisted that “[r]eligions operate on and consist of, make and are made by bodies.” [i]In the last fifteen years, perhaps this is no more overtly expressed than via Muslim women’s bodies. The sight of a (veiled) Muslim woman harkens so much speculation: Why is she veiled (or not)? What role do the men in her life play in her life decisions? Is she formally educated? Does she have a job? Ultimately, is she oppressed? [ii] This fixation with Muslim women functions as a facade for a deeper fixation with Islam writ large in a post-9/11, post-Arab Spring, ISIS-dominated context: these questions center on Islam yet play out on Muslim women, whose bodies remain its material markers. At the same time, they remain material markers of politics. For at least the past twenty years, Morocco has pointed to the position of Moroccan women to mark its location within the Muslim Arab world and the Middle East and, ultimately, its ideational, political, economic and geographic proximity to Europe. [iii]Politics, economics and religion playing out on women’s material bodies.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, in Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, offer a theoretical tool we can use to approach the political and economic significance of bodies. Here they define a social machine as “literally a machine, irrespective of any metaphor.” [iv]Laborers - cogs - plug into profit-producing wheels that together form machines. Alongside them, dominant classes (re)produce desire by modeling lack and abundance: laborers lack the material abundance of dominant classes. Desire is a “revolutionary institution” [v]: subjugated groups - here, laborers - carry the potential to explode a group’s dominant position by “grinding and breaking down” social machines “in spasms of minor explosions.” [vi] I suggest that we merge Morgan’s insistence on bodies in the study of religion with the materiality of Deleuze and Guattari’s laborers: religion and culture merge in material embodiment and, ultimately, politically-saturated material religion.

To illustrate this materiality, I point to Death for Sale, Bensaïdi’s third feature-length fiction film following his 2003 Mille Mois and 2006 What a Wonderful World. In all three, he relies much more on cinematography than spoken words; scenes often contain very little dialogue while he favors long shots and the “poetry” of camera movement. [vii] His stories make visible the traces of globalization saturating twenty-first century Morocco by focusing on those who exist on Morocco’s margins: they’re not the radically, overtly violent and thereby highly-visible characters we see, for example, in Nabil Ayouch’s 2012 Horses of God, a fictionalized account of four of the twelve suicide bombers in the 2003 Casablanca attacks. [viii]Instead, the three male lead characters are merely petty criminals who, as Bensaïdi says, “never killed anyone.” [ix]

Death for Sale is set in Morocco’s northern coastal city of Tetouan. It’s not Tangier, its sister city an hour to the west: it’s not famous for being a former international zone, for Paul Bowles or William Burroughs. It’s much quieter, much smaller. The same is true of Malek (Fehd Benchemsi), Allal (Mouchine Malzi) and Soufiane (Fouad Labied) around whom the film revolves. It opens as Allal leaves prison having served time for selling drugs - northern Morocco’s famous hashish - not as one of Tetouan’s drug lords but as a small fish in a big pond. They all are: we watch Soufiane return to an orphanage, Malek to his sister, mother and uncle-cum-stepfather above the bakery that was his father’s. Rather than work with his uncle, who’s taken over the bakery, Malek picks up cash by snatching purses alongside Allal and Soufiane.

Meanwhile, his sister Awatef (Nezha Rahile) is onscreen very briefly yet makes a significant visual impact, forcefully articulating the absence of personal and professional choices available to myriad lower-class Moroccan women sans formal education, stable employment or economic freedom. Paradoxically, she is also her family’s primary breadwinner: she works in a textile factory, one of many located across Morocco’s coastal cities, literally fighting her way each morning through crowds of other women also trying to find a way in. She supplements her family’s income by smuggling out clothing labels that Malek then sells. She’s a cog, yes; she’s also one of Deleuze and Guattari’s schizophrenics, flowing between center and margin, normality and neurosis, never really participating in society like she’s expected to yet never violently exploding the system. She leaves that to Malek. And yet their family’s focus ultimately rests on her, not him: her actions, her body, draw its attention and its ire.

Bensaïdi, I argue, makes visible our fixation with Muslim women’s material bodies in how he films Awatef. We first see her alone, centered in the family living room. Rather than using a medium shot or even close-up to situate her as our focal point, Bensaidi uses a long shot. She’s lost in the scene’s visual chaos: the vertical lines of the carpet on the wall behind her paralleling the vertical lines of the columns in front of her, the horizontal lines of the couch, the table that stands between her and the camera, the bright light above her that drowns her out. We can’t really see her here. And we often see her here, with their mother and uncle attentively serving her tea when she returns from work while Malek lays on the couch in the bottom corner of the screen, staring away from them toward a television. Both she and he are small, insignificant. Moroccan culture dictates that it should be him earning the family’s money, not her. The hagara - shame - so pervasive across Morocco permeates them both because they both function outside of the parameters set for them by Moroccan cultural norms and expectations.

Figure 1: Awatef amidst the visual chaos of her living room

Figure 1: Awatef amidst the visual chaos of her living room

Awatef haunts Morocco: the space between Africa and Europe, poor and privileged, local and global economy, Morocco’s maraboutism (a blend of Sufism and Sunni Islam) and more textual iterations of Islam such as Wahabism. She’s born of the culmination of 1960s and 70s nationalist efforts by King Hassan II popularly known as The Lead Years, his radical shifts in economic policies in the 80s and reconciliation efforts in the 90s, [x] Mohammed VI’s accession in 1999 and the cumulative imprint of globalization on twenty-first century Morocco: It retains high illiteracy rates, especially among rural and lower-class women (in excess of 60%), [xi] a broken education system, increasing wage gaps and rising unemployment. Morocco gained global attention in 2003 when twelve suicide bombers carried out coordinated attacks across Casablanca and again in 2004 as Mohammed VI resisted a reputation for Islamic fundamentalism by announcing a new moudawana (family code) ostensibly offering women more rights in marriage, divorce and child custody. [xii]Awatef, I argue, sits at the intersection of these socio-economic, political, cultural and religious realities.

Malek meets and, at first sight, falls in love with Dounia (Imane Elmechrafi), a prostitute at the once-chic, now decidedly second-rank Pasarella Club. He does everything he can to attract her attention, including spending all he earned selling Awatef’s contraband on whiskey and prostitutes so he can watch her with other men. Meanwhile, always quieter, Awatef convinces him to cover for her as she slips away for the weekend with Omar. “Are you sure he’ll get divorced?,” Malek asks as he walks her to work one morning. “Yes, but when he told his wife, she tried to commit suicide.” “And you believed him?,” Malek retorts. “I’ve told you, first chance he gets he’ll leave you for someone younger.” Here Awatef and Malek are shot from above: the high angle traps them against the concrete sidewalk that serves as our backdrop.

Figure 2: Awatef and Malek discussing Omar

Figure 2: Awatef and Malek discussing Omar

Malek leaves Awatef, returning to the pre-dawn darkness; she, meanwhile, cuts her way through a crowd of women. Cut: the camera opens on a medium shot of her at her sewing machine. This is the first time we seen her at a proximity and in lighting that allows us to make out her facial features. Yet this scene is so very chaotic and closed: she’s boxed in by the sewing machine before her, the other women and their machines behind her. As the bell rings - the end of the work day - the camera cuts to a high-angle shot of the factory floor. Vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines intersect: metal light fixtures, rows of sewing machines, bodies filing out the back of the frame. Patted down and passing inspection, Awatef returns to darkness. She went in at dawn; she leaves at dusk.

Figure 3: Awatef at her sewing machine

Figure 3: Awatef at her sewing machine

Figure 4: Awatef lost in a sea of machines

Figure 4: Awatef lost in a sea of machines

Hassan II’s structural readjustment programs yielded market liberalization as well as exponential growth in multi-national corporations and unemployment. [xiii] Fast forward to 2004: the new moudawana made Awatef, as an unmarried woman, a legal adult rather than a minor. She can travel alone, without a guardian’s permission, yet she still needs Malek to cover for her. Legally, she’s free; culturally, she’s still dependent on him, her uncle, her reputation. She’s indelibly marked by Hassan’s restructuring and Mohammed’s moudawana, fighting her way into the factory and smuggling out something as materially immaterial as clothing labels. She’s our schizophrenic revolutionary: a ‘minor explosion’ that, alongside others, carries the potential to grind against Morocco’s social machines. As her mom helps remove the labels from inside her bra and around her waist, as she moves to the couch and her mom serves tea, Malek is also boxed in: into the front of the frame. We almost miss him. Such is the reality of post-restructuring Morocco: lots of brothers are unemployed; many walk their sisters to work each day.

Figure 5: Awatef flanked by her mom and uncle; Malek in the lower right corner

Figure 5: Awatef flanked by her mom and uncle; Malek in the lower right corner

Walking together to where Omar is waiting, Awatef tries to convince Malek to meet him. It’s too complicated, he says. Bensaïdi films her so differently here: until now, we’ve only seen her before dawn or after dusk, dressed in a long djellaba. Here, she’s wearing a dress, drenched in afternoon sunlight and backed by bright open space. The shot has a depth of field; it’s full but not chaotic. Here, in terms of cinematography, she’s free, unbound. In following her desire, is she exploding the social machines surrounding her? Until now, we’ve not clearly heard her voice; she’s only talked quietly with Malek or her mom. Now, as she and Malek go in different directions, she clearly calls out his name. Handing her bag to Omar, she runs to him, hugs him. This is the last time she speaks.

Figure 6: Awatef in bright afternoon sunlight on her way to meet Omar

Figure 6: Awatef in bright afternoon sunlight on her way to meet Omar

Figure 7: Awatef saying goodbye to Malek

Figure 7: Awatef saying goodbye to Malek

We see her once more, once again in the chaos of a closed form. Everything about this scene is different than the one before. She sits in a car staring out the window; standing outside, out of focus, Omar smokes a cigarette. As he opens the door and drops into the driver’s seat, a tear slides down her cheek. She never looks at him, never speaks to him, staring blankly away. Her aunt surprised them all by coming to Tetouan for the weekend. The same aunt whom Malek told their mom and uncle she was visiting. Awatef’s aunt and mom work to convince her uncle Awatef and her aunt simply passed each other on the train; he doesn’t buy it. And while Malek fixates on getting Dounia out of jail for a prostitution charge, Awatef locks herself in his bedroom and hangs herself. We don’t see her do this: Bensaïdi never shows her after that tear. Instead, we hear about it through Malek and her mom. A spasm, a minor explosion, sans visual confirmation.

[ ]((/assets/images/uploads/moody/death-for-sale/Screen-Grab-8.jpg)

Figure 8: Awatef and Omar

]((/assets/images/uploads/moody/death-for-sale/Screen-Grab-8.jpg)

Figure 8: Awatef and Omar

Did Awatef commit suicide because her family found out? Because her uncle reacted with rage? Because she realized Omar wouldn’t leave his wife? Did she desire Omar or the abundance he modeled? The answers to these questions are less important than the material realities they represent. Morocco points to Muslim women to demonstrate its moderate expression of Islam as it intersects with modern (read: Western or neoliberal) economic and political structures. Yet the material realities of this moderation don’t trickle down to lower-class women, rural women, women without formal education or economic stability. To me, Awatef demonstrates the importance of seeing material religion among material bodies in material, quotidian realities.

Notes and References

- [i] David Morgan. “The Material Culture of Lived Religions: Visuality and Embodiment,” Material Religions , accessed 3 June 2015.

- [ii]See, for example, Lila Abu-Lughod, “Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving?: Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others,” American Anthropologist 104:3 (September 2002): 783-90.

- [iii] See, among other sources, Samia Errazzouki, “Working-class women revolt: gendered political economy in Morocco,” The Journal of North African Studies 19:2 (2014): 259-67.

- [iv] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem and Helen R. Lane (New York: Penguin Books, 2009, 1977), 141.

- [v] Ibid., 31.

- [vi] Ibid., 151.

- [vii] Tiffany Vazquez, “Interview: Faouzi Bensaïdi, ‘Death for Sale,’” filminc.com, 10 April 2013, available from http://www.filmlinc.com/blog/entry/interview-faouzi-bensaidi-death-for-sale-morocco-african-film-festival, accessed 3 June 2015.

- [viii] Avouch often uses extreme violence to illustrate daily realities of Morocco’s poorest citizens. See, for example, his 2000 Ali Zaoua: Prince of the Streets. His films also draw significant controversy. Before even applying for a permit, his upcoming Zin li Fik, focusing on Morocco’s rampant sex industry, was banned in Morocco.

- [ix] “Interview: director Faouzi Bensaïdi (Death for Sale),” worldcinemaamsterdam.nl, available from http://www.worldcinemaamsterdam.nl/nl/menu-types/1075-interview-director-faouzi-bensaidi-death-for-sale, accessed 3 June 2015.

- [x] See Susan Miller, A History of Morocco (_Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013) and Susan Slyomovics, _The Performance of Human Rights in Morocco (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005).

- [xi] Shana Cohen and Larabi Jaidi, Morocco: Globalization and Its Consequences (New York: Routledge, 2006), ix.

- [xii] See Zakia Salime, Between Feminism and Islam: Human Rights and Sharia Law in Morocco (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2011).

- [xiii] For much more on Morocco’s market readjustment programs, see Cohen and Jaidi’s Morocco: Globalization and its Consequences and Shana Cohen, Searching for a Different Future: The Rise of a Global Middle Class in Morocco (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004).