Affects of Consumption and Commodification in a Moroccan Ramadan

Rebecca Moody narrates her impressions of commodification and consumption during Ramadan in Fes, Morocco, through a series of ‘still lifes’. By paying attention to the power of the ordinary as affects and traces, Moody encourages us to pause and contemplate how the sacred and the secular are mixed in daily life. Never separated, they flow into each other, carried by the everyday struggles and celebrations of bodies and minds in this sacred month in the Islamic calendar.

When I was in high school, I worked in a drug store. In addition to dispensing little red and blue pills, I spent a fair bit of time behind the perfume counter selling all manner of tsotckhe.The craziest day of the year, the last possible minute people could purchase presents for parents and partners alike, on Christmas Eve I sprayed endless samples of mediocre-smelling lab-manufactured liquids and wrapped them in sparkly red and green paper. Watching yet another guy stroll toward the counter; dropping yet another box atop thick paper adjacent an oversized roll of scotch tape. These were my Christmas Eve still lifes: “static state[s] filled with vibratory motion.” [i] For brief moments, life was still: a frozen image capturing the store’s and the season’s “liveness,” suspending their “sensory beauty in an intimate scene charged with the textures of paint and desire.” [ii]

It’s something many people have come to know and loathe, no matter what, if any, religious tradition we practice: tangible affects associated with the consumption and commercialism of Christmas. Still lifes of elaborately decorated trees cluttered beneath with brightly adorned boxes. Whether the lived materiality of Christmases past or the seemingly requisite Hollywood banality that captures however fictitious ‘textures of paint and desire,’ many carry them with us. They suspend traces of materiality and flows of materially coded affect that have come to represent a convergence of sacred and secular. Similarly, Ramadan in Fes, Morocco brings the “affective contagion” that further blurs already contested sacred - secular lines. [iii] Here, drawing on what Kathleen Stewart calls ordinary affects, I navigate these contested lines and examine the material objects and practices that get caught up in the commodification of Ramadan. I will pause on still lifes: moments that make visual these blurrings of sacred and secular life. Via their significance, I will illustrate the potential impact of incorporating affect into the study of material religions. Pulsing within the ordinary - “a shifting assemblage of practices and practical knowledges” [iv]- ordinary affects “give everyday life the quality of a continual motion of relations, scenes, contingencies, and emergences.” [v] They’re physical, material, bodily while also ephemeral, fleeting, fluid: “They work not through ‘meanings’ per se, but rather in the way that they pick up density and texture as they move through bodies, dreams, dramas, and social worldings of all kinds.” [vi] Stewart builds on Raymond Williams’ structures of feeling: “social experiences” that are “still in process.” [vii] Her ordinary affects and his structures of feeling merge public and private: both are “public feelings that begin and end in broad circulation, but they’re also the stuff that seemingly intimate lives are made of.” [viii] Rippling across surfaces of quotidian life, they are seen and felt, even if unspoken.

The ninth month of the Islamic calendar, Ramadan commemorates the time when the Prophet Mohammed began receiving from God the revelations that yielded the Qur’an. It’s considered by many Muslims to be the holiest time of the year; it’s also associated with one of the five pillars, or acts that most Muslims consider mandatory (making a public declaration of faith, praying daily, giving charity, fasting during Ramadan if one is physically able and making a pilgrimage to Mecca if one is physically and financially able). Ramadan is most visibly marked by the materiality of fasting: during daylight hours, Muslims refrain from eating and drinking, smoking and having sex. Ideally, they also refrain from cursing and all manner of impure thoughts and actions. Such restraint offers the mental and physical space necessary to focus on more important aspects of spiritual life. It’s a liminal space, to be sure: simultaneously part of and beyond ordinary time that differently yet collectively binds together many of the world’s Muslims in extended still lifes.

Figure 1: A marker of Ramadan on an otherwise bare wall in the Batha neighborhood of Fes. There one day, it was painted over the next. Image by author.

With Ramadan’s approach, across Fes a “weirdly floating ‘we’ snaps into a blurry focus” as the materiality of rhythms, rituals and practices become collectively regular. [ix] Daily routines synthesize around fasting, which in turn revolves around the five daily prayers: f’jer at dawn; dhour at midday; ‘asr in late afternoon; maghreb at sunset; ‘isha at night. Muslims fast between f’jer and maghreb: sunup and sundown. S’hor (suhur in Fus’ha: standard academic Arabic) - a light meal - immediately precedes f’jer; fasting follows until the maghreb prayer and f’tour (iftar in Fus’ha): breakfast, literally breaking the fast. The poetry of the corresponding verse in the Qur’an beautifully registers this collectively ordinary rhythm: “[E]at and drink until the white thread becometh distinct to you from the black thread of the dawn. Then strictly observe the fast till nightfall” (2:187).

My first Ramadan in Fes, I was surprised when s’hor fell closer to 3:30 am than 5:30 or 6:30, as I tend to think of sunrise. The f’jer call to prayer billows from mosques’ minarets just as a faint streak of pinkish-grey light appears in the distance: during Ramadan, ‘sunrise’ happens far before the sun’s disk breaks the horizon. This liminally ordinary space pulses with collectively ordinary differences. Sitting at my table at 3:00 am eating s’hor, I look out my window and notice many other silent lights in windows up and down the street. Collectively rhythmic, collectively liminal, collectively ordinary: on any other night at any other time of the year, these same windows would be dark, these streets would be a different kind of quiet: instead of small groups of young men noisily making their way home from cafes, instead of small groups of d’raya-clad (abaya in Fus’ha) men meandering toward mosques, they would be much more deserted, the silence more palpable. To be certain, not all Muslims fast during Ramadan, just as not all Christians attend church during Advent nor all Jews temple on High Holy Days. It nevertheless remains one of Islam’s most visible moments for Muslims and non-Muslims alike, and many Fassis take it very seriously. Even if one does not pray daily or attend weekly juma’ (sabbath) services, does not observe other manner of conduct thought proper for practicing Muslims, chances are likely that this same Fassi will fast during Ramadan. And not simply a public display of fasting with a private consumption of food or water. So strict is Ramadan in Fes that Fassis warn of the dangers of being in the wrong place at the wrong time (the few hours immediately before breaking the fast): even addicts - however “[r]ogue intensities roam[ing] the streets of the ordinary” [x] - refrain from using their drug of choice during fasting hours so that the closer they get to f’tour, the more they physiologically crave the substance that follows the maghreb call to prayer. Collectively rhythmic, collectively liminal, collectively ordinary affects that “give thing the quality of a something to inhabit and animate.” [xi]

Consult most any guidebook and you’ll likely find the following trinity: Casablanca is Morocco’s financial capital, where the majority of national and international corporations are based; Rabat the political capital, where the parliament is housed and King Mohammed VI most often makes his home; Fes the spiritual capital: the medina (old city), dating to the eighth century C.E., is dotted with mosques, madrasat (Islamic schools) and centuries-old Sufi tombs-cum-Muslim and Jewish pilgrimage cites; it also boasts the world’s oldest continually-operating university: al Qarawiyyin, founded in 859 C.E. by Fatima al Fihri (a woman!). Fes takes this mantle seriously. Its historic and contemporary, quotidian and tourist identities revolve around it and the materiality it yields: the tourist dollars that flow from all manner of people seeking what they expect - and thus find - as frozen-in-time exotic spiritualism; its reputation in Casablanca and Rabat as a secular and sacred outlier, Morocco’s wild west. It’s not at all uncommon to see myriad, however complex and contradictory, mash-ups of sacred and secular, old and new, beldi (traditional or rural) and romi (modern or urban, a remnant of another, much earlier colonizer: the Roman empire).

As Ramadan approaches, the flows and pulses of Fes’ sacred and secular build in expectation and excitement into some_things. By its start, however-blurred collective _we’s snap into place as most every ordinary routine changes. Not in the same way for every Fassi, of course, but most everyone’s day flows in some significantly different ways. It’s h’shuma (shameful) to sleep past the midday prayer as it defies the spirit of the fast. Still, many teens find creative ways to stay up far past f’jer and sleep until just before maghreb. Government offices shift their hours to exclude a lunch break: rather than working from 9 am to 6 pm with a two-hour lunch, employees work from 10 am to 4 pm. Many spend this extra time reading the Qur’an in the mosque or at home; some will read the entire text. Within and without the mosque, many shift their dress to include more traditional jellaba and d’raya. Other daily routines begin to change in the weeks and months before its start: popular Fassi religious convention holds that a fasting Muslim should not consume alcohol in the forty days before Ramadan begins. According to many, the body needs all forty days to completely metabolize alcohol. Whether or not one believes it, many still heed the warning.

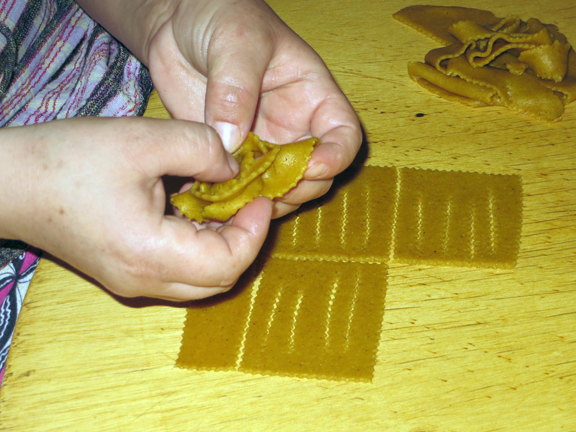

Beyond changing personal habits, public markers also populate Ramadan’s approach. A few weeks before it starts, stands weighed down with mounds of honey-drenched pockets of sweetness begin to pop up in neighborhoods far and wide. Shabbakia is Ramadan’s ubiquitous treat: a pastry made from ground almonds and sesame seeds. The involved sweet is mixed and molded, kneaded and folded, rolled flat, cut and shaped into little lotus flowers, fried in oil, boiled in honey and sprinkled with sesame seeds. Kilo upon kilo tempts passersby; those manning the stands keep them fresh by daily drenching them with more honey. Families early identify their stand of choice and buy literally buckets of shabbakia that then grace their f’tour tables every evening, offering a burst of calories and protein. Among the luckiest Fassi families, groups of women gather to make their own. The women in my adoptive Fassi family spend whole days - three or four in total - making the many kilos that they will serve and send to extended family. Chopping, rolling, cutting, folding, frying, boiling… these are time-intensive treats, to be sure. On these days, other markers of their daily lives blur into the background much like a scene in a film that lacks depth of focus. Lunches become smaller and more impromptu; children scamper around the house as all available adult hands roll, cut and fold. A collective we snaps into place.

Figure 2: Halwa (sweet) stands in the Fes medina. The tall mounds partially wrapped in plastic are shabbakia. Image by author.

Figure 3: The first step in making shabbakia; mixing the dough. Image by author.

Figure 4: Cutting and folding shabbakia. Image by author.

Figure 5: One of the many trays we rolled, cut and folded. Image by author.

Figure 6: My bucket of shabbakia. By the end of Ramadan, it was depleted. Image by author.

Ramadan pulses with consumption that is truly ordinary, truly material, truly fluid, collectively public and private. Beyond its time-intensive process, shabbakia is expensive, be it store-bought or homemade. This year, in the days before it started, the price of almonds increased significantly, from between 60 and 80 MAD (Moroccan dirham) per kilo to 120 and even 140. Thus, they’re not immediately within the price range of the average Fassi, though many work to find the cash. Neither are the dates that accompany shabbakia on most every breakfast table and with which most Fassis break their fast: the Prophet did so with three dates, many have told me; they follow his advice. As the cost of almonds and dates skyrocket, so, too, does that of other Ramadan staples: oranges for fresh-squeezed OJ; tomatoes for h’rrira (Morocco’s famous soup), even apples and bananas increase steadily higher. Thus, a time of year marked by daily fasts is also marked by the affective tumult over how to pay for food. These ordinary capitalist pulses ripple across the surface of quotidian life: families quietly yet collectively worry about where to find the cash; these worries are whispered in most every house across some neighborhoods. Collectively rhythmic, collectively liminal, collectively we: “the ordinary affect on the textured, roughened surface of the everyday.” [xii]

Beyond the capitalist pulse of food prices, Ramadan’s collective rhythms revolve around the body’s physiological response to fasting: those many hours sans food; those few when one replenishes the calories and liquids, caffeine and nicotine previously denied them. It’s a constant and competitive cycle, given that Ramadan currently falls during the summer. Daily fasts lasted more than sixteen hours this year; the solstice brought the year’s longest day and, thus, its longest fast. Fasting, then, makes material the fluidity of ordinary affects: they ebb and flow, however slightly evolving with each ebb. The Islamic calendar is lunar; thus, Ramadan moves by about two weeks every year. If the calendar completes a cycle roughly every thirty years, then in fifteen Fassis will be fasting in January, when daylight hours are fewest and the risk of extreme dehydration at its lowest. This will yield much shorter fasts and different f’tours, with a focus on calorie intake over fluid. But that’s then, not now: ebb and flow. Many Fassis spent this year rehydrating after f’tour as temperatures consistently topped 100 F / 40 C. Sixteen consecutive hours in that heat without water makes for a severely dehydrated body. And for all the ordinary routines that ebb, others do not: all manner of manual laborers continue to labor in the midday heat. Privately, out of the public eye, the collective pulse of the second shift also remains static: a recent report published by Le Haut Commissariatau Plan, a monarchy-funded statistical analysis office, showed that between paid work and domestic labor, women work an hour and a half more each day during Ramadan than the rest of the year. Collectively ordinary, collectively liminal, collectively and rhythmically familiar yet fluid.

It’s an exhausting schedule that wears one down physically and emotionally. As Ramadan creeps into its third and fourth week, the number of car accidents and physical altercations (sometimes but not always related) rises noticeably. Fassis grow ever more distracted, ever crankier. I met a friend late one afternoon in a cafe that technically wasn’t open (to the confusion of many tourists, most remain closed until f’tour). Seeing me, he exclaimed, “you’re fasting!” I asked how he knew. “Your eyes,” he said; “those dark circles are a telltale sign.” It’s true: faces physically change as the month wears on. The snap of a collectively blurred we. Suffice it to say that by f’tour, I want water: crisp, delicious nectar of the gods. My kidneys be damned, as the call to prayer sounds in the background, I quickly grab my date and just as quickly pound a glass of shockingly cold water. Ordinary affects that pulse with material, bodily intensity. I find similar pulses of near-crippling need among even the most faithful Fassis: in the sheer exhaustion and simultaneous satisfaction on my Fassi mom’s face as she swallows her first taste of cold milk. Lifting the glass to her mouth, she closes her eyes; returning the glass to the table, eyes still closed, she releases a quiet, contented sigh. Her affect merges with others around her: a private yet public collective we. Following f’tour, I find it hard to balance my body’s near-constant cravings for fluids and food; I’m constantly amazed by how many consecutive hours of drinking I need before I began to feel hydrated. And at just that time: s’hor. The materiality of Fassis’ fasts - materiality that “shimmer[s] with undetermined potential and the weight of received meaning” [xiii] - effectively registers Ramadan’s collectively ordinary affects.

Nightlife also flows between sacred and secular. As my Fassi family gathers for f’tour, its patriarch performs ablutions, grabs three dates and meanders toward the mosque. He eats the dates with the maghreb call to prayer, prays, then returns home for f’tour. After completing the cooking, my Fassi mom eats a date and drinks a glass of milk with the call to prayer, moves to the bedroom to pray, then returns to eat. A quick breakfast - prayer - a more proper f’tour: the fluidity of sacred and secular, the snap of a collectively blurred we. After f’tour, women and men together move from their f’tour table to the mosque for the ‘isha prayer, to perform tarawih - supplementary Ramadan prayers - and to listen as f’kih (prayer leaders who have memorized the Qur’an; faqih in Fus’ha) recite the Qur’an. Following tarawih, some return home to sleep until s’hor. Other men move to nearby cafes, prayer mats under their arms, to sip coffee and talk with other men while women stroll arm-in-arm around their neighborhood. After sitting or strolling for a few hours, they head home to sleep, get up at around 2 am for s’hor, return to the mosque for f’jer and then to their beds for a few more hours. Collectively rhythmic, collectively ordinary, collectively we. It’s only within the last few years that people have increasingly been staying up until s’hor before sleeping. Ebb and flow.

Ramadan’s materiality, its affective flows, its collective we’s reach their apex on the 27th night: Laylat al Qadr, the night of power, when the Prophet began receiving the revelations: “Lo! We revealed it on the Night of Predestination. Ah, what will convey unto thee what the Night of Power is! The Night of Power is better than a thousand months” (Qur’an 97:1-3). If Fassis spend any night in the mosque, it’s this one. Some stay all night: f’tour through s’hor. Prayers offered on the 27th night, when Allah and angels come closest to earth, are worth a thousand others.At the same time, in recent years the 27th night has become increasingly visible in other ways: parents (for now, mostly moms) traditionally dress their young children - in caftans or jellabas, balgha (shoes) and tarboush (aka: a fes) - and wander around their neighborhoods. Girls’ hands and feet are decorated with henna; many have their hair and makeup elaborately done. Capitalizing on the night’s financial possibilities, most anyone, it seems, with the necessary equipment sets up elaborately decorated stands. Girls sitting in ‘amaria (large round chairs) are hoisted above the shoulders of zarzaya who chant shabi (popular wedding music) or issawa (more traditional Fassi music) as they present the girls to gathering crowds, much as at a wedding. Boys, meanwhile, take their turn on henna-stained horses. All of this is caught on camera and video and sold to proud parents. Still lifes.

Figure 7: The 27th night. A young girl dressed in a caftan on Laylat al Qadr in Fes. Image by author.

Public and private pulses, ebbing and flowing intensities, evolving we’s: as its location on the Gregorian calendar changes, as does jellaba fashion, so, too, does the clash of Ramadan’s sacred and secular shift. The 27th night is increasingly anticipated more for parades of children than tarawih prayers, and therein lies the source of disagreement: some claim that these parades are h’shuma (shameful); people should be at the mosque. On the 27th night, Fes’ “cultural landscape vibrates with surface tensions spied or sensed.” [xiv] Ebbs and flows are emergent: we seldom have words for them. Instead of seeking stable meanings, Stewart suggests we “slow the quick jump to representational thinking and evaluative critique long enough to find ways of approaching the complex and uncertain objects that fascinate because they literally hit us or exert a pull on us.” [xv] We sense the ebbs and flows of ordinary affects: they materially prick us, and therein lies the significance of collective we’s on material religions. My Fes family - eight children, the youngest of whom is 28 - didn’t participate in the parades: they simply didn’t take place. Their young children, however, do_._ With each manifestation of the materiality of Islam’s holy month, Fes’ collective we snaps into collectively blurred, collectively evolved ordinary affects. They’re materially important, significant, even if subtle: even if they only ever exist on the vibrating surface of quotidian life.

And just when I think I can’t possibly fast another day, just when I think Ramadan’s still life is forever frozen and the month will never end, it’s Eid S’ghir (the little holiday). In Islam, fasting is prohibited twice each year: Eid S’ghir (Eid al Fitr in Fus’ha) and Eid K’bir (the big holiday; Eid al Adha in Fus’ha). Think of Eid S’ghir as Mardi Gras and Thanksgiving rolled into one. Not in the turkey, certainly not in the beads, but in the ordinary affect: the collective joy. Catholics celebrate Mardi Gras in anticipation of their 40-day Lenten fast; Muslims celebrate after Ramadan. Those who pray do so at sunrise not in a mosque but a m’salah (from salah, to pray): an open area on the outskirts of town. Thousands pray together, collectively we, in the early morning sun. Just as women spent the days before Ramadan making shabbakia, they spend the days before Eid S’ghir making all manner of halwa (sweets) and gateau (cake, from the French word). After returning from m’salah, they enjoy them alongside pots of Morocco’s famous mint tea. A few hours later, the extended family gathers for lunch. I spent Eid with thirteen adults and six children. They laughed, told stories and ate their first lunch in a month. Collectively, joyously, and, in the end, full-bellied.

Figure 8: M’salah on the outskirts of Fes. Image by author.

Figure 9: Another view of the same M’salah. The crowds spilled out of its walls. Image by author.

Notes

- [i] Kathleen Stewart, Ordinary Affects (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 19.

- [ii] Ibid., 18.

- [iii] Ibid., 16.

- [iv] Ibid., 1.

- [v] Ibid., 1-2.

- [vi] Ibid., 3.

- [vii] Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 132.

- [viii] Stewart, Ordinary Affects, 2.

- [ix] Ibid., 27.

- [x] Ibid., 44.

- [xi] Ibid., 40.

- [xii] Ibid., 39.

- [xiii] Ibid., 23.

- [xiv] Ibid., 45.

- [xv] Ibid., 3.