Marginal Maps

Samuel Tongue merges book history, marginalia studies, reader usage, cartography, and cultural geography to theorize the inclusion of maps as an example of biblical marginalia in 16th-century printed Bibles. By examining a specific example of a user adding their own marginal map, Tongue focuses on religious, historical and economic forces that undergird their authority, arguing that, for a certain user, these maps produce an imagined ‘Palestine,’ framing the land as stage for a divine history, while also underwriting the ‘truth’ of the biblical texts in a type of cartographical Protestant geopiety.

Glasgow University’s Special Collections contains a 1537 ‘Matthews’ (Tyndale-Coverdale) Bible with some fascinating marginalia. An unidentified bird’s muddy footprints march across the beginning of the prophet Nahum, prompting questions as to where this Bible was kept during its everyday life. In addition, and opposite the title page is a hand-drawn chronological table showing the time elapsed since various biblical events up to 1651, presumably the year in which the owner wrote it in.

However, my interest lies in the rude sketch of a Holy Land map, bearing the same graphological signature and, as is evident from placing the two Bibles alongside one another, clearly copied from a 1560 Geneva Bible: Why might the owner have perceived his bible as somehow lacking in relation to the scholarly and parabiblical material included in the Geneva Bible? What material conditions made it possible for the cartographic scribbler to complete this fascinating example of biblical marginalia? And what are the implications of producing such territorial inscriptions?

Image 1: Copy-Specific detail of hand-drawn Holy Land Map in The Byble: which is all the holy Scripture: in whych are contayned the Olde and Newe Testament / truly and purely translated into Englysh by Thomas Matthew. M,D,XXXVII, Set forth with the Kinges most gracyous lyce[n]ce. University of Glasgow Special Collections. Photo by Robert Maclean.

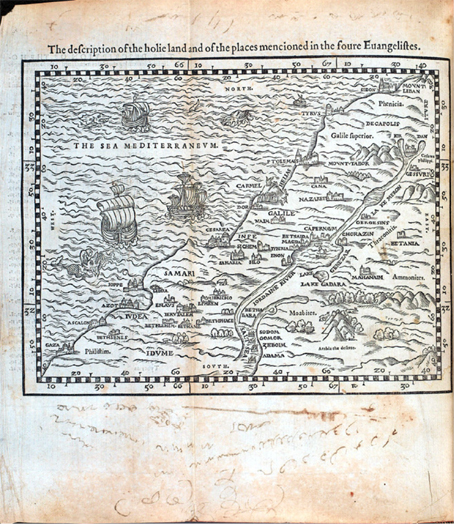

Figure 2: Holy Land map from 1560 copy of Geneva Bible.

Maps in Bibles arise within a complex nexus of historical and theological contexts prompted, in no small part, by the development of print media. Travelling across the disciplines of book history (and print Bibles in particular), marginalia studies, reader usage, cartography, and cultural geography, my focus is on the inclusion of maps in 16th-century printed Bibles: why are they included and how does this intersect with what Edward Said has called an “imaginative geography,” J. B. Harley a “subliminal geometry,” and, in a particularly useful formulation, what Burke O. Long terms ‘geopiety’, “that curious mix of romantic imagination, historical rectitude, and attachment to a physical place” [i]—in this case, a distant, idealised, and constructed ‘Holy Land’? As I shall explore, these maps exist on a spectrum of imagined Holy Lands, beginning in the biblical texts themselves, moving into pilgrimage accounts and on to large, free-standing mappae mundi and broadside imperial maps, right up to contemporary Holy Land parks and guided tours of supposedly ‘biblical’ sites. In this way, geopieties are formed and informed by different types of media interaction. What I want to suggest, is that, for a certain Bible user, these 16th-century maps produce an imagined ‘Palestine’ constructed around biblical characters’ lines of movement, framing the land as stage for a divine history, whilst also underwriting the ‘truth’ of the biblical texts in a type of cartographical Protestant geopiety.

‘Andro Duncan’ In terms of the provenance of this ‘Matthews’ Bible, Duncan claims ownership of the book in 1672, proudly writing on the flyleaf that “Andro Duncan is my name and for to writ think not sheam”. We are immediately confronted with the medium of the printed book and how it allows a user a certain level of interplay with the text. As Heather Jackson notes, “all the front area of a book, from the inside of the front cover to the beginning of the text proper, presents an opportunity to provide introductory material, and the first impulse of any owner appears to be the impulse to stake a claim” [ii]. This sense of ‘staking a claim’ is important and I shall explore this further below. After examining the map and the penmanship around it, it is highly probable that Duncan is the cartographic copier. I shall not attempt to construct Duncan in great detail, as a reader, actual or implied; for my purposes, Duncan serves as a cipher for the questions I want to outline and explore - I hope not to ‘sheam’ him in the process.

The Bibles, side-by-side In order to get a sense of the context of Duncan’s scribbles, a brief note on the Bibles that he is using is pertinent. Duncan’s Matthews Bible, printed in Antwerp in 1537, earned its name from its ascription to “Thomas Matthew commonly taken to refer to the names of a disciple of Christ and an evangelist in order to form a pseudonym for John Rogers, a one-time associate of [William] Tyndale,” [iii] who edited what is essentially Tyndale’s work but also included Miles Coverdale’s translation of the Apocrypha. Tyndale had been executed at Henry VIII’s command only a year before the publication of this version although, with a dark irony, the Matthews Bible would form one of the main sources for the King’s Great Bible of 1539, the first authorized edition of the Bible in English.

However, according to John King and Aaron Pratt, the Matthews version failed to “gain traction even though it furnished what became the primary basis for later versions […]. The Matthew translation and its revisions […] were published in only nine among close to two hundred Bible and New Testament editions produced prior to the King James Bible” [iv]. With this in mind, it is noteworthy that this is the Bible that Andrew Duncan is using nearly one hundred and fifty years later in 1672 and possible reasons for this will be explored further below.

The second Bible is the 1560 English Geneva Bible. With its thorough revisions of the Great Bible [v], in particular those books that Tyndale had not translated [vi], and its “most profitable annotations upon all the hard places” (from the title-page), this version became the household Bible of English-speaking Protestants in the 16th-century. In more outspokenly Calvinist Scotland, with its links to Geneva through John Knox and other exiles, “the Geneva Bible was from the beginning the version appointed to be read in churches” [vii] and it was actually the first Bible printed in Scotland in 1579.

The mise-en-page of the Geneva Bible was novel: “it was printed in roman; it divided the text into verses, so as to facilitate the use of a concordance; words supplied in order to render the translation idiomatic were printed in italic; books and chapters were supplied with ‘arguments’; and summary running titles were provided” [viii]. However, for all its novelty, it also, infamously, includes extensive discursive marginal notes, “similar to manuscript and early printed commentaries” [ix] belying some of the Reformers’ protestations to let the text speak for itself. With this popular printed format in mind, it is easy to see how this version is seen as the first ‘study’ Bible to be put into the hands of vernacular readers.

Much has been made of the textual apparatus yet little work has been done on the maps that are included in the Geneva Bible. If one lays the two Bibles alongside one another, it is clear that Andrew Duncan has compared them and decided to copy the Holy Land map into his own. This felt need is made manifest in this unique piece of marginalia, not scribbled around or into the text at the opening to the New Testament where it is bound in the Geneva Bible, but placed right at the very beginning, even before the beginning, of his Matthews Bible. But where does this map come from and what functions might it be serving for Duncan?

Biblical Maps and the Printing of Protestant Geopiety Catherine Delano-Smith and Elizabeth Morley Ingram have covered this topic in fantastic detail, examining over 1000 Bibles and New Testaments, including at least one copy of every recorded 16th century English edition of the Bible. Interestingly, only 176 editions contain maps and “they occur primarily in full Bibles rather than in New Testaments” [x]. The maps are also included in Dutch, English, and German Bibles and French editions published in Switzerland or in Swiss-influenced parts of France; as Delano-Smith and Ingram make clear, “the history of maps in Bibles is part of the history of the Reformation” [xi].

The Holy Land map we are concerned with appeared as one of four new woodcut maps printed in Nicolas Barbier and Thomas Courteau’s French Genevan Bible (1559): “Two of the maps relate to the Old Testament (Exodus, the Division of Canaan among the twelve tribes), and two to the New (Palestine in the time of Christ, the Eastern Mediterranean for the journeys of Paul). All four maps appear to have been made specifically for this Bible and are announced on its title-page” [xii]. Barbier draws attention to the “four chorographical maps of great use and consolation” (‘quatre cartes chorographiques de grande utilité et consolation’) and explains that their purpose is “to present clearly to the reader’s eye what is otherwise difficult to grasp from the text alone” (‘pour representer au vif devant les yeux ce qui seroit plus difficile a imaginer & considerer par la seule lecture’) [xiii]. These four maps “were published again, from different woodblocks, in the following year in Rouland Hall’s English translation of the Genevan bible, also published in Geneva” [xiv]. This ‘set of four’, along with the addition of John Calvin’s Eden map, provide an exceptional example of consistency in map design. They were used as a more or less complete set by at least twenty-four different publishers for forty-eight different editions of the complete bible in nine languages in many countries for half a century. They were copied and recopied. Yet each remained to all intents and purposes identical. [xv]

As Delano-Smith and Ingram highlight,

the maps also, no doubt, had a commercial function. Like other illustrations in the Bibles, they were a selling point as their advertisement on title pages indicates; and like other illustrations, they were costly. Publishers and printers could economise by borrowing existing map blocks or by copying prints. Such commercial restraints must explain, at least in part, the quite astonishing faithfulness of so many Genevan map copies from 1559 onwards, and their overall durability. [xvi]

The Genevan Bible is an enhanced Bible and thus eminently more marketable, targeting those users who appreciate the utility and ‘consolation’ of maps and other apparatus. But this remains a theological market – the maps also demonstrate the Protestant view of the primacy of scripture over doctrine and emphasize “both the historical reality and the eschatological promise of scripture by demonstrating its geographical setting” [xvii]. The Holy Land map serves as an illustration, supplementing the text, and adding a visual, imaginative dimension to be read with the biblical accounts.

The commercial constraints on production and the durability of these illustrations in printed Bibles ensures that they reach a wide public [xviii] and goes some way to accounting for Duncan’s awareness of and desire to copy the Genevan map. The medium of a printed map raises some interesting questions relating to its usage however, particularly around the intersections of early modern cartographical thinking and knowledge production.

There is much debate in book history circles over whether the development of printed material led seamlessly to the “diffusion of the Scientific Revolution of the seventeenth century, the Protestant Reformation and the Renaissance” [xix]. Some scholars make the point that the dissemination of a more ‘scientific’ cartography can be married to a sense of uniformity in print, “a vital development for reference works like maps […] [which] would have little credibility if the reader knew that every copy was unique” [xx]. Yet it is important not to overstate the case for print’s accuracy and fixity per se. As Adrian Johns has asserted, “early modern printing was not joined by any obvious or necessary bond to enhanced fidelity, reliability, and truth. That bond had to be forged” [xxi].

Yet, in the case of the Geneva maps, geographical accuracy is not the primary aim and it is here that we can see one of the key outworkings of the maps printed in Protestant Bibles. These maps, “as art and not just like art, became a mechanism for appropriating the (sacred) world by categorizing it in the manner approved by the religious authorities” [xxii]. The bonds that compel Andrew Duncan to sketch his map are formed from the religious, historical, and economic forces that undergird the authority of the map: even as late as 1672, this is the map that he wants as, through its repetition in printed Bibles, it is now an authorized cartography of Palestine, an aid to his own locating of the peregrinations of Jesus and his disciples across the text.

Andrew Duncan’s Marginal Map Through an accident of its material production, Andrew Duncan’s old Matthews Bible opens up a substantial marginal space, providing the opportunity for what Kate Narveson terms the “imaginative control of one’s self-understanding” [xxiii]. Evelyn Tribble suggests that marginal notes on the early-modern printed page demonstrate “a territory of contestation upon which issues of political, religious, social, and literary authority are fought” [xxiv]. Yet Duncan’s scribbled map sits at a complex nexus of material uses of the Bible and he seems uninterested in contesting biblical authority. Rather, he utilises this space to underwrite received authority with his own sketched copy. Heather Jackson argues that “the Bible is a prototype of all especially treasured and pored-over volumes […]. It attracted supplementary materials, almost as an act of worship, certainly in a spirit of reverence” [xxv]. Perhaps due to the high cost of a purchasing a King James Version [xxvi], Duncan has procured a Geneva Bible from which to copy his Holy Land map and constructs this hybrid Matthews Bible. This supplementary map is a detailed aide-memoire that is a performance of his own geopiety; through his lines of ink and penmanship, he travels imaginatively and with graphological flourish across this biblical page.

However, his marginal sketch is also central to understanding the “cartographic image in a social world” [xxvii]. The Geneva Bible, in its innovative layout and marginal apparatus, invites imitation; as Jackson notes, printed editions of “the Bible and of classical and vernacular literature provided models of scholarly annotation that readers could extend to works of their own choosing […] the book itself providing the system of organization” [xxviii]. The Geneva Holy Land map invites Duncan to reproduce it in the white space of his Matthews Bible, where he does not question its validity as a map per se, but confirms its cartographic authority as “part of the intellectual apparatus of power” [xxix]. Alongside the ownership marks, Duncan is careful to copy in the note indicating that his sketch is a ‘description of the holie land and of the places mentioned in the foure euangelistes’. This cartographic means of ‘staking a claim’ sets the scene for a geopiety that fuses an unvisited land with an ‘imaginative geography’, maintained by a combination of textual authority and widely disseminated biblical maps. This map does not stand isolated and alone; it is part of a mesh of other contemporary cartographical works, existing alongside other Renaissance and early-modern exegetical visualisations of the Holy Land: histories, atlases, and “mural map cycles designed for both sacred and secular settings” [xxx]. These maps do not function as mirrors but are producers of a specific cartographic world-view that anchors theological exegesis in an idea of the real, historical world. But this has other consequences. The woodcut map from the English Geneva Bible also depicts three 16th century galleons carving up the Mediterranean; Duncan includes one of his own, quite literally a ‘ship of the line’. In this way, this unique and reverential marginal map participates in the cartographical thinking that claims and colonises lands on paper, anticipating other lines of power, ultimately justified by a God’s-eye view [xxxi]. As John Pickles notes, “maps provide the very conditions of possibility for the worlds we inhabit and the subjects we become” [xxxii]. For the geopious subject, the biblical map is nothing less than the sketching out of the divine entering the measurable, mappable ‘real’.

###Acknowledgment: The author would like to thank Robert Maclean, Assistant Librarian at Glasgow University Library’s Special Collections, for drawing his attention to the Matthew’s Bible.

References:

- Bruce, F. F. The English Bible: A History of Translations. London: Methuen, 1963.

- Delano-Smith, Catherine. ‘Maps as Art and Science: Maps in Sixteenth Century Bibles’. Imago Mundi 42 (1990): 65–83.

- Delano-Smith, Catherine, and Elizabeth Morley Ingram. Maps in Bibles 1500-1600: An Illustrated Catalogue. Geneva: Librairie Droz S.A., 1991.

- Harley, J. B. ‘Maps, Knowledge, and Power’. In The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design, and Use of Past Environments, edited by Denis Cosgrove and Stephen Daniels, 277–312. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Ingram, Elizabeth M. ‘Maps as Readers’ Aids: Maps and Plans in Geneva Bibles’. Imago Mundi 45 (1993): 29–44.

- Jackson, H. J. Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

- Johns, Adrian. The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- King, John N., and Aaron T. Pratt. ‘The Materiality of English Printed Bibles from the Tyndale New Testament to the King James Bible’. In The King James Bible after 400 Years: Literary, Linguistic, and Cultural Influences, edited by Hannibal Hamlin and Norman W. Jones, 60–99. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Long, Burke O. Imagining the Holy Land: Maps, Models, and Fantasy Travels. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2003. Lyons, Martyn. A History of Reading and Writing: In the Western World. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- McMullin, B. J. ‘The Bible Trade’. In The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain: 1557-1695, edited by John Barnard, D. F. McKenzie, and Maureen Bell, 4:455–73. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. - Narveson, Kate. Bible Readers and Lay Writers in Early Modern England: Gender and Self-Definition in an Emergent Writing Culture. Farnham and Burlington: Routledge, 2012.

- Pickles, John. A History of Spaces: Cartographic Reason, Mapping and the Geo-Coded World. London and New York: Routledge, 2003.

- Said, Edward W. ‘Invention, Memory, and Place’. In The People, Place, and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, William Mangold, Cindi Katz, Setha Low, and Susan Saegert, 361–65. New York and London: Routledge, 2014.

- Tribble, Evelyn B. Margins and Marginality: The Printed Page in Early Modern England. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 1993.

- Watts, Pauline Moffitt. ‘The European Religious Worldview and Its Influence on Mapping’. In The History of Cartography, edited by David Woodward, 3 (Part 1): 382–400. Chicago & London: Chicago University Press, 2007.

Endnotes:

- [i] Burke O. Long, Imagining the Holy Land: Maps, Models, and Fantasy Travels. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2003), 1.

- [ii] H. J. Jackson, Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 19.

- [iii] John N. King and Aaron T. Pratt, ‘The Materiality of English Printed Bibles from the Tyndale New Testament to the King James Bible’, in The King James Bible after 400 Years: Literary, Linguistic, and Cultural Influences, ed. Hannibal Hamlin and Norman W. Jones (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 67.

- [iv] Ibid.

- [v] The Great Bible of 1539, prepared by Myles Coverdale, was the first Bible authorised by Henry VIII to be read in Church of England churches. Much of the material comes from William Tyndale, with Coverdale providing material missing from Tyndale’s original.

- [vi] F. F. Bruce, The English Bible: A History of Translations (London: Methuen, 1963), 89. [vii] Ibid., 92.

- [viii] B. J. McMullin, ‘The Bible Trade’, in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain: 1557-1695, ed. John Barnard, D. F. McKenzie, and Maureen Bell, vol. 4 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 456. Notwithstanding Conrad Badius’s publication of an English New Testament in 1557 (translated by the English exile William Whittingham) which is the first English Bible to include both chapter and verse divisions.

- [ix] King and Pratt, ‘The Materiality of English Printed Bibles from the Tyndale New Testament to the King James Bible’, 77.

- [x] Catherine Delano-Smith and Elizabeth Morley Ingram, Maps in Bibles 1500-1600: An Illustrated Catalogue (Geneva: Librairie Droz S.A., 1991). xvi.

- [xi] Ibid.

- [xii] Elizabeth M. Ingram, ‘Maps as Readers’ Aids: Maps and Plans in

- Geneva Bibles’, Imago Mundi 45 (1993): 29.

- [xiii] Ibid., 30.

- [xiv] Catherine Delano-Smith, ‘Maps as Art and Science: Maps in Sixteenth Century Bibles’, Imago Mundi 42 (1990): 67.

- [xv] Ibid., 73.

- [xvi] Delano-Smith and Morley Ingram, Maps in Bibles 1500-1600: An Illustrated Catalogue, xxix.

- [xvii] Ibid.

- [xviii] Ingram, ‘Maps as Readers’ Aids: Maps and Plans in Geneva Bibles’, 39.

- [xix] Martyn Lyons, A History of Reading and Writing: In the Western World (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 26.

- [xx] Ibid., 33–34.

- [xxi] Adrian Johns, The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 5.

- [xxii] Delano-Smith, ‘Maps as Art and Science: Maps in Sixteenth Century Bibles’, 77.

- [xxiii] Kate Narveson, Bible Readers and Lay Writers in Early Modern England: Gender and Self-Definition in an Emergent Writing Culture (Farnham and Burlington: Routledge, 2012), 6.

- [xxiv] Evelyn B. Tribble, Margins and Marginality: The Printed Page in Early Modern England (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 1993), 2.

- [xxv] Jackson, Marginalia, 182.

- [xxvi] See McMullin, ‘The Bible Trade’.

- [xxvii] J. B. Harley, ‘Maps, Knowledge, and Power’, in The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design, and Use of Past Environments, ed. Denis Cosgrove and Stephen Daniels (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 303.

- [xxviii] Jackson, Marginalia, 184.

- [xxix] Harley, ‘Maps, Knowledge, and Power’, 282.

- [xxx] Pauline Moffitt Watts, ‘The European Religious Worldview and Its Influence on Mapping’, in The History of Cartography, ed. David Woodward, vol. 3 (Part 1) (Chicago & London: Chicago University Press, 2007), 395.

- [xxxi] Harley, ‘Maps, Knowledge, and Power’, 282.

- [xxxii] John Pickles, A History of Spaces: Cartographic Reason, Mapping and the Geo-Coded World (London and New York: Routledge, 2003), 5.