Matters of Place: Placing Religion in Film

M. Gail Hamner explores the place of religion in film where, beyond cartography, place is relational: indexed in an at once individual and collective where, what and when. Beyond tracking actual and tangible places such as the Vatican or American West, religion in film is about what she calls affecognitive economies that offer expression for felt if unthought responses to those places. Hamner’s attention to film form, including light and sound, and to the sedimented histories of certain places further offer ways of feeling the violences that not only mark our current world filmicly but that also inundate our daily lived lives.

These are the redacted comments I gave at the opening of the Ray Smith Symposium, “The Place of Religion in Film” at Syracuse University, March 31, 2017. The conference was graced with participants from 10 countries and 10 US states. My thanks to all the participants and to plenary speakers—Sara Horowitz, June Hwang, and Joaquim Pinto—for their high caliber writing and thinking.] [i]

The land on which Syracuse University is built is sacred and stolen land. It is, in fact, the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the People of the Longhouse who form the historic Confederacy made up of Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas. For some years now, faculty at S.U. are in the habit of opening conferences, lectures, and workshops with a statement like this about the stolen ground that undergirds everyday life at our university. Such collegial insistence to name the violence of the past and to note its persistence in our shared present is amplified by the current social and political situation in the United States. Weekly, if not daily, we hear about assaults and crimes against non-white and non-cis persons, groups, and bodies: incidents of minorities being told to “go back to your own country,” transgendered women murdered, Sikh men murdered, a teenaged Muslim girl murdered, another (again) African American man killed by the police and the officer exonerated, swastikas appearing on school lockers and front lawns, nooses appearing on the grounds of the African-American Museum of Culture and History, and TSA and ICE officers acting with unusual force. In early March 2017, a white supremacy group called “Vanguard America,” which carries the web address of bloodandsoil.org, organized the so-called “The Texan Offensive” in which they “put up…[white supremacist and anti-Muslim posters] at Texas State University, Rice University, the University of North Texas, the University of Texas at Dallas, Collin College, Abilene Christian University, and Louisiana State University…”

It may not be true, but it feels as if these acts are occurring in ideological deference to the mounting Federal (and mutating) threat of deportation hanging over immigrants and refugees. And it may not be true across the board, but I would bet that the persons committing these acts wish to forget, deny, or violently erase the history of non-white presence on this land. They wish to forget, deny or violently erase the history of mass genocide of indigenous peoples, the horrors of chattel slavery, and the persistent flow onto this continent of non-white and white immigrants. In this context, to assert vociferously the history of place—to assert that any place is held together by a physical and relational matrix that brims with stories and lives, with factions and contestations, with sacred relationship, with life and death, with joy, and love, and loss—seems today a crucial and necessary act of resistance.

Lately, I have been reflecting on film as a public, as a medium of publicness and a mediation of certain publics. By this I mean not only that a film text can be read and interpreted for its social messages, but also that the success of a film is measured in part by its success in either fitting contemporary discourse on an issue like a glove, or pushing that discourse to change. How does the history of place show itself in the medium of film? How is the sacredness of place displayed and anchored? When I think about the broad rubric of the place of religion in film, I think first about the many physical places that evoke religion or take on religious valence in certain films: churches, mosques, synagogues, and specific religious cities or monuments (e.g., Jerusalem, the Vatican, the Kaaba, statues, totems, crucifixes); the vast landscapes of the American West; national monuments; niches of memory and ritual in cityscapes or homesteads; and woodland groves or forest clearings with pools or waterfalls.

But then my philosopher proclivities kick in and I wonder about this term place. I wonder about its capaciousness and how its wide pliability speaks also to the wide variability in what counts as historical representation and as cultural memorialization. These days in the academy place is often conjoined and opposed to space, where the latter is something logical or mathematical, while the former is more existential [ii]. Space can be Newtonian, denominating the container for experience and events. Or space can be, as it was for Kant, the a priori condition of possibility for human experience. Or we can conceptualize space vis-à-vis the grids of urban and rural territories that mapped and codified the earth’s vastness in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when the commons was closed and private property expanded. Soon afterwards the oceans became territorialized, and the vastnesses between the planets stood as space’s final frontier.

Place on the other hand slots into the experiential and evental. Space might be open to orienting technologies like cartography, but place orients someone or something in some specific manner. In other words, place is relational. Place is nothing in itself but is the felt suture of a where to a what and a when, that is, to the idiosyncrasies of specific histories and memories, both collective and individual. The relational construction of place calls us to attend to the power differentials deployed or suffered in one and the same place (but is it the same place?), and to record and reflect on how history and memory differently refract the winners and losers of those power struggles in the lived edges, pits, and vortices of place. Near my home here in Syracuse is an old Roman Catholic Church, the membership of which declined to the point where the parish was unable to maintain it. They sold the building and now Holy Trinity Church is the Mosque of Jesus Son of Mary. What is interesting—not completely surprising, but worthy of reflection—is that some of the former worshippers at Holy Trinity are angry that the crosses have been removed and slowly replaced by crescents. Somehow they could understand and even embrace the pragmatic consequences of generational change and a shrinking budget, but the affective charge of place, of this place as a Christian place (even as my Christian place), was too strong to keep Islamophobic anger at bay.

All of the above can be reiterated by asserting that, like the concept of religion, the concept of place is multitudinous and richly textured. Something quite different from place vs. space, for instance, can be found in Stoic philosophy. The Stoics theorized place as subsisting between the incorporeal void and all that forms the corporeal. Place is not the void and place is not a body, but rather stands as the transition between them. Place is where bodies can take shape and do things [iii]. This sense of place as mediation and support is unfamiliar and curious, but it might be fruitful to consider it alongside particular filmic frames or in conjunction with Gilles Deleuze’s sense of “camera consciousness.” In his Cinema books Deleuze notes that the camera can function as a brain not only by tracking objects and events, but more importantly by enabling thought-felt connections that blur subject-object and the temporal registers of past, present, and potential [iv]. Aligning religion with this sense of place might lead us to consider orientations that are unthought but felt, that are not nothing, but also have not yet been actualized into material practices or structures. Put differently, the place of religion in film—when place is mediation and support—draws us to analyze how religion is not only about tracking certain named subjects, objects and events, but is also about diffuse and mutating affecognitive economies that supersede objects without superseding materiality, and that settle into lived assumptions and yearnings for the kind of significance, wholeness, or beauty that exceeds capture by the quotidian empirical.

Do the history, memory, and power of place require bodily expression? And if so, what is a body? Are there bodies outside of place or are bodies only formed in conformation to specific places? What does it mean to be a body present but out of place? Can the bodily nature of place be sensorially formed between and across bodies, instead of felt inside of bodies? In other words, where does analysis take us if we posit that the experiences that mark space as place might be virtual or affective instead of actual and tangible? How does it matter, and what difference does it make if bodies are theorized as personal and collective (persons in and as a crowd or network or rhizome), instead of personal and singular (an individual, a self, an autologic subject)?

Because religion entails marking persons and places in particular and various ways and for particular and various ends—though of course religion entails many other things, too—all that I have said about place and bodies pertains as well to the place or placing of religion in film.

Consider, for instance, the many actual and tangible places that are compelling to analyze as the places of religion in film, such as the monastery in Xavier Beauvois’s 2011 release, Of Gods and Men, or the floating temple in Kim Ki-duk’s 2003 film, Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter…and Spring [v]. These structures are Eliadean, built to evoke or attest to hierophanies; they are portals or places of liminality that are experienced (by characters and viewers) in ways that are both extraordinarily intimate and personal and also magnetically collective, even universal. Indeed, the interplay between the intimate and universal plays off the grim weight of norm and expectation (the monks’ vowed life in service to God; the death faced by each of us) and rippling, diffuse light of the seasons of love and life that are reflected differently by different characters, according to their understanding of and response to the histories and memories they find in and bring to these places.

Caption 1: Xavier Beauvois, Of Gods and Men (2011)

#wideCaption 2: Kim Ki-duk, Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring (2003)

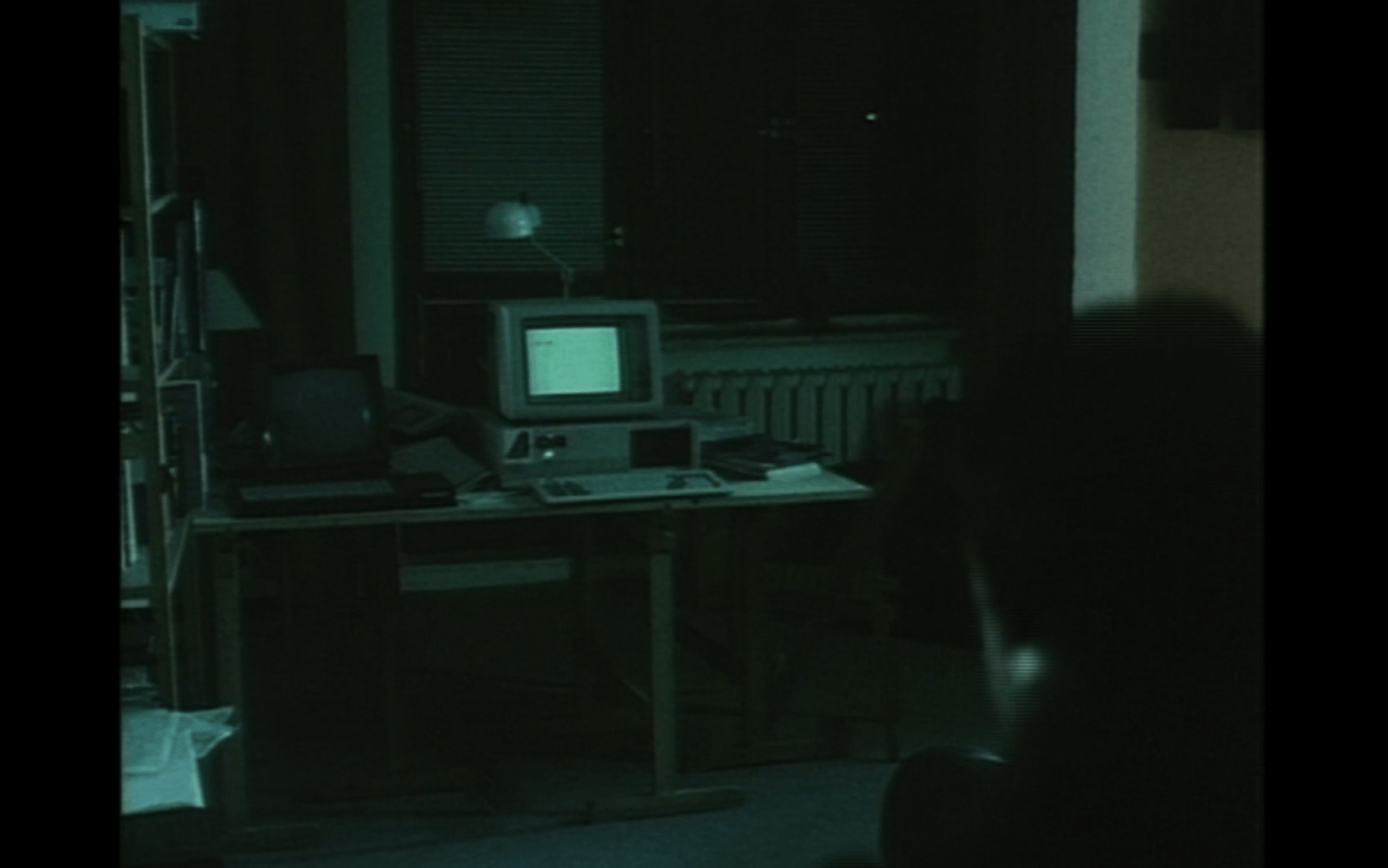

Consider, too, how religion is sometimes marked or placed much more obliquely and ambivalently than these Eliadean structures, for example through the eerie green computer glow in the first of Krzysztof Kieslowski’s 1989 TV series, Dekalog; through the novitiates’ rituals with and around the statue of Christ in Pawel Pawlikowski’s 2013 release, Ida; or through the ocean scene between Juan and Little in Barry Jenkins’s stunning release from last year, Moonlight.

Caption 3: Krzysztof Kieslowski, Dekalog (1989)

Caption 4: Pawel Pawlikowski, Ida (2013)

Caption 5: Barry Jenkins, Moonlight (2016)

These films demonstrate how light, ritualized relationship, and elemental interaction all might evoke and play with the places of religion. They do so by each differently connecting a where to a what and a when. Each differently forms a nodule of affection that is something like a pincushion—a ‘place’ (held in practice or in memory) that receives the sharpness of the world and softens it by transvaluing it. The world’s confusion becomes the intelligence of algorithm in Dekalog; the world’s ugliness becomes Christ’s beauty and devotion in Ida; the world’s brutality becomes a place of loving touch and care in Moonlight.I think, further, of how something like Buddhist compassion is evocatively constructed through the Dalai Lama’s slowly placed gazes in Martin Scorsese’s Kundun, or how something like Christian transcendence is placed between the screen and the viewer through the music of John Tavener in Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men and of Beethoven’s Sonata no. 8 (“Pathetique”) in the Coen brothers’ The Man who Wasn’t There.

Caption 6a: Martin Scorsese, Kundun (1997)

Caption 6b: Martin Scorsese, Kundun(1997)

Caption 7: Alfonso Cuarón, Children of Men (2006)

Caption 8: Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, The Man who Wasn’t There (2001)

Cinematography, montage, and soundtrack, patterned and sutured over the temporal arcs of the film build up and set in motion affective orientations, virtues, and ineffable hopes that work materially but non-verbally on characters and viewers alike, and that mark—or shift, or expand—the place of religion in film.

Taking quite a different tack, consider how films can show the sedimentation of religious sensibility and practice in transversal places of social conflict such as Ismaël Ferroukhi’s 2011 Free Men (les homes libres), Abu-Assad’s 2005 Paradise Now, or Julie Dash’s 1991 Daughter’s of the Dust. These films engage the place of religion and the violence of history through the crisscrossing of precarious Muslim, Jewish, Christian, and state spaces: Nazi-held Paris in 1942; the borderlands between cosmopolitan, Jewish Israel and poverty-stricken Muslim Palestine (with a Christian “last-supper” scene thrown in for good measure); and the intersecting times, memories, objects, words, spirits, and gods connecting Africa, the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina, the West Indies, and the US mainland. The religious histories and practices in these films are imaged less through a place and more through the movement through places, or (and) through the collapse of one kind of place (e.g., Muslim) into another kind of place (e.g., a hiding place for Jews). In these films the visible transversality of place forms palpable affective tensions and constructs and constricts the social, political, and religious possibilities of their characters. Sometimes, too, religion is placed and moved by elemental forces, such as the rain in Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai or the wind in Yojimbo and also (but differently) in John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt, and water in all its phases in so many of Terrence Malick’s films, including Tree of Life, To the Wonder, and Knight of Cups. Here we are exposed to the material, earthy incarnation of religion as the concomitant or interruptive presence of an elsewhere or otherwise (or elsewise and otherwhere). Water and wind sculpt the places of religion as much as does landscape.

Caption 9: Julie Dash, Daughter’s of the Dust (1991)

Caption 10: Hany Abu-Assad, Paradise Now (2005)

Caption 11: Akira Kurosawa, Seven Samurai (1954)

Caption 12: Terrence Malick, Tree of Life (2011)

Finally, sometimes the place of religion moves with a single object that does not even register as religious, like the parrot in Kon Ichikawa’s The Burmese Harp, the mask in Ousmane Sembene’s Black Girl, or the car in Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry and Ten. The religiosity arises not from these objects themselves, and not from the spaces through which they travel, but rather from the setting of the object in the mise-en-scène and its relational and symbolic use by characters and director. In other words, objects suture the intangible (incorporeal) places of religion in film to a material but nonetheless happenstance visible object.

Caption 13: Ousmane Sembene, Black Girl (1966)

In each of these examples, the places of religion in film are also the religiosities of place, enfolding the confluent histories, experiences of violence, and possibilities for compassion that all places, placing, and religion(s) inhere [vi]. To me, the joy and task of analyzing religion in film emerge in wrestling with difficult and unexpected senses of materiality, of place, and of religion such as the ones to which I have gestured in this post. I suggest we hold to the etymological root of perception (per + capere = entirely + to take or grasp) in order to be inspired toward analyses that entail, indeed that require grasping affectively and conceptually the interplays of tightly-held practices, beliefs and traditions with cinematic form, pace, lighting, narrativity, and mise-en-scène, in order to grant full-bodied voice and material weight to the legacies of theft, assault, agony, and other violences that arise from these material perceptions of place. Considering the suffering places of our current world, this methodology seems a necessary anchor, frame, and ballast for any discussion of the place of religion in film.

Endnotes

- i. The list of persons and departments I owe for supporting this conference is long. Here I wish only to acknowledge the specific material, organizational, and temporal contributions of Rebecca Moody, Deborah Pratt, and Mohammed El Hamzaoui.

- ii. See Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Minnesota, 2001).

- iii. See Elizabeth Grosz, The Incorporeal: Ontology, Ethics, and the Limits of Materialism (Duke, 2017), 32ff.

- iv. Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image, 24 (Minnesota, 1989).

- v. All images are screen-grabs I made from DVDs I own.

- vi. Laura Marks, Enfoldment and Infinity: An Islamic Genealogy of New Media Art (MIT, 2010).